Evaluation, Reflection, and Assessment

Evaluation

The classroom environment enables children to demonstrate what they know through a variety of authentic assessment strategies (exhibitions, demonstrations, journals, group discussions, debriefings, interviews, and conferences). Assessment is constant and ongoing so as to identify students' strengths and learning approaches as well as their needs. Teachers observe play, watch children drawing, listen to conversations and ask questions. As children explain their thinking, teachers can assess their level of understanding. "Students points of view are windows into their reasoning. Awareness of points of view helps teachers challenge students, making school experiences both contextual and meaningful. Each student's point of view is an instructional entry point that sits at the gateway of personalized education" (Brooks & Brooks 1993, p. 60).

Documentation is vital for assessment. Documentation includes narratives of child to child conversations, child to adult conversations, photo portfolios (photo narratives), wall displays, and written summaries. Documentation offers opportunities for children to evaluate their own work, for teachers to keep parents better informed (knowledge web), and for teachers to gain a better understanding of how children learn. Documenting conversations and representations at the beginning and at the end of the project for the group as a whole and for each individual child gives perspectives of growth in all dimensions including vocabulary, concepts, knowledge, skills and dispositions.

Tomlinson's "Planning Model for Academic Diversity and Talent Development" (Tomlinson, 1996, p. 162) is a useful tool for examining how children's responses showed growth. Instead of using the model to differentiate instruction, the teachers have used it to examine how responses to the activities were differentiated among students as well as how they demonstrated growth in students throughout the study. In a project-based classroom, where many activities are open-ended, using Tomlinson's indicators can show growth. Teachers can demonstrate through child portfolios how children have gone from simple to more complex responses; concrete to more abstract understandings, and less independence to more independence in work habits and dispositions.

In an environment of inquiry, teachers look for evidence of children's growth (Klein & Toren, 1998). Children's questions may evolve from general to more specific once children have more knowledge about a topic. They may transfer their learning by making links to other things that they know and with which they are familiar. They may incorporate the new vocabulary into their every day language. Teachers look for growth in fluency of ideas and in ways in which children generate questions, solutions, hypotheses and theories. Teachers look for growth or change in students' understandings by examining artifacts of learning which include drawings, structures, writings, and conversations. Children may also become more self-directed, more engaged, and may strengthen their dispositions to inquire, to assume responsibility, to persevere, and to take on leadership roles within a group.

The evaluation of a project investigation includes teacher reflections, student self-evaluations, parent-feedback, and an examination of each child's project portfolio to assess growth and learning. Two examples of children's project portfolios are included in this document.

Teacher Reflections

Before the project began, the teachers noticed most every child having many, varied experiences building and constructing with a variety of materials in the classroom. Common experiences and interests serve as foundations for questions and increased understandings. The topic of construction was both concrete (building) and fun (sand castles, Legos, blocks). At the same time, the topic lent itself to complexity (building sequence, relationships between construction and the environment, properties of materials etc.) that allowed for children to be challenged and grow.

The primary method of assessing what children have learned is through the documentation of experiences. In a multi-age classroom, there is a diversity of learning exhibited. Teachers notice children's thoughts expressed through surveys, conversations (discussions both whole group and small, incidental interactions and problem-solving), writings, observations, predictions, stories, representations, and progress in the beginning of the project. Teachers can compare individual children's depth of understanding at the end of the project with what was evident at the beginning of the study.

Children started the project with a varied background of experiences. A class survey was taken on October 10.

Do you have construction going on by your house?

The results showed 10 answering yes, 15 answering no.

On October 1, a survey questioned,

Have you every visited a construction site?

11 answered yes, 14 answered no.

The surveys demonstrated that many children were not aware of construction sites.

During the first brainstorming discussion (Construction Topic Web I), some children showed their lack of experience by only being able to say a few ideas that they knew or could remember about construction.

|

EA: Workers wear hard hats. |

Others commented on personal experiences or sightings.

|

LM: I have made a crane. |

Teachers also noted misconceptions in the brainstorming.

|

JB: Bulldozers can't scoop, they are for pushing things. |

The children studied construction over a period of months, which also allowed for in-depth inquiry and research towards understanding. The teachers found it rewarding to see the depth of the children's investigations and to see the growth in the ability of young children to take the lead in their study. In the Teacher's Construction Topic Web, the teachers planned the anticipatory concepts inherent in the project. One big idea that arose from a question in Phase 1 was "Why do we need buildings, such as skyscrapers?"

From a sample of the following conversation, most children appeared to understand why buildings were needed.

|

AH: No rain can get in on us. |

The relationship between construction, buildings, and the environment was a researchable question. A child expressed this question.

|

CM: How do they talk people into letting them crash buildings to build other buildings? |

Several children made a special point of interviewing the site manager with questions.

|

CO: How do you decide where you are going to build? |

JP found out that the plants needed to be moved to a different location because the building was being built where the plants were planted. In the Student Construction Topic Web II, SL concluded that construction workers did not care about plants.

Another big idea in the teacher's web was knowledge of the tools, machines and process or sequencing of building. As written in Phase 1, some children argued about the sequence. One child's misconception provided the opportunity for other children to observe closely, ask questions, and learn about the sequence of building.

|

HB: Construction workers start to build from the top. I have seen them up high. |

The final Student Construction Topic Web II of "What I Now Know about Construction" showed the increased number of children who paid attention to the sequencing of building.

Teachers anticipated children would increase in their vocabulary and knowledge of tools, materials, machines and building parts and become more aware of the fields of architecture and engineering. Most children had noticed construction on their drive to school each day. However, during the first brainstorming of ideas, it was apparent that one child (EA) had not been aware of construction and could not name a single idea without teacher encouragement. After the construction project was finished some children defined new vocabulary words. Teachers noted the growth for EA when she talked about what she would tell a friend about construction. She stated her definition of a claw hammer; "A claw hammer has 2 ends on the back to get out a nail if it's bent."

Using pictures taken on a field trip several weeks earlier, children talked about what they were doing in the photographs. Again, teachers noted the increase of specific names for tools, building parts and facts about construction whereas earlier children would misname machines and tools or refer to parts of the building as "that thing".

|

JB: In the picture, I was asking questions to the construction

site manager who was building the Football Practice Facility. We

talked about an arch, which was also called a truss, which holds

up the roof. I asked him what types of materials he used. He said

that he used concrete, steel, metal, and cement. |

Teachers can see evidence of growth and change of understanding in children's drawings, writings, and structures. The students grew tremendously in using various media to represent construction. Making three-dimensional structures out of paper and cardboard seemed to be a new experience for many. The teachers guided children's work by asking questions.

How do you plan to attach one pipe to another?

What are you planning to attach this wall to?

How did that pipe work out?

What has not worked so far?

How did you know that this would be the right size?

Children wanted to represent structures with sand, blocks, cardboard and graham crackers. Their representation of their individual buildings also helped them become quite familiar with the sequence of constructing and their individual knowledge was transferred to the construction site knowledge.

Children reflected, wrote and drew what they had learned about construction. Many wrote about what they had learned from experts and secondary sources. Others wrote about the results of experiments or observations they had completed during field study. Several children defined construction by saying what construction does. Some children's comments revealed that they became more aware of construction and construction sites. All students developed in-depth knowledge in the areas that they studied.

The students also matured in their dispositions. Cooperation was quite important in Phase 3 for the group-constructed models of a building, crane and dump truck. It was interesting to see how responsibly the children questioned each other (child - to - child) during "progress reports" at group meetings. Teachers watched children becoming more articulate in presenting their perspective and giving reasons to back up their opinions. These discussions helped each group to clarify their thoughts and plan for an improved representation.

The children applied problem solving skills and mathematical and critical thinking as they created group models of a building, crane and dump truck. They listened to each other, and learned how to appreciate others' ideas, articulate disagreements, and posed questions for clarification. A comparison of Student Construction Topic Web II and Student Construction Topic Web I showed an increase in fluency and understanding of construction.

Student Self-Evaluation

Children showed evidence of learning when they independently chose activities related to the construction topic. In reflecting about the whole semester, the children wrote and drew about things they liked about the construction project.

|

HB: I like the crane. |

Students' Responses to Interview Questions

1. What would you tell a friend about construction?

Talk about wrecking balls at the museum. JN

About cranes' rope. AH

I've seen lots of construction around my own house. I saw lots of cranes and dump trucks. EA

They can build high buildings and low buildings. HB

Tell about dump truck. NC

Tell about cranes. BC

How they build cranes. JH

People build big houses and small houses, skyscrapers, all in different sizes. SJ

How to build stained glass windows. Put food coloring on it. WJ

Do you know anything about construction? I saw my neighbors building a sunroom with lots of windows. AK

It takes 150 days to build a house. KK

That there are different kinds of cranes and vehicles of construction. CM

How I went to the big dig with seven tower cranes. JM

The cranes go on the top of the building as the building gets higher to build a skyscraper. LM

About a forklift. NO

They can build when they grow up. CO

Tell about the machines. JW

Cranes look like they go high just like fire trucks, but cranes' baskets don't go as high. ER

How balls to from one container to the dump truck and how they get dumped out' like your brother's toy construction set. KS

Would they know if cranes lift heavy things like 254 pounds or not? CS

Tell them about al the names of the dump trucks and cranes. SL

Construction is hard to do. You have to use so many materials and it takes too long (5-6 years). JD

2. What would you like to keep doing with construction?

Make a building like a skyscraper. JN

My food construction. AH

I'm all done. ER, CM, EA, HB, JH, SJ, AK, LM

Building a cardboard building. NC

Building our car. BC

Keep building the cardboard house. WJ

Making the cardboard houses. KK

Drawing building and construction vehicles. JM

Keep making my cardboard house and my bed. NO

Nothing. CO

Keep working on my house. JW

Keep working on box with pipes, like the construction site. KS

Keep working on my two cardboard buildings. CS

Building construction vehicles. SL

Study more about dump trucks. JD

3. What are you still wondering about construction?

How stairs are built. JN

Why do they have to use the machine to crack the window when the window is broken, instead of carefully getting them out by hand? AH

How do they make stained glass windows? EA

How can they build floors without standing on them? Where do they stand while they're building the floor? HB

How does a forklift lift 800 blocks? NC

How do cranes lift up 200 blocks and move at the same time. BC

How the blue thing lifts wood. JH

How do they put the walls on? SJ

Nothing. WJ, CM, CO

I am not that interested in construction. I'm willing to participate, but I'm not really interested. AK

How do they know how to build a house underground with a bomb in it and blow it up? KK

How cranes pick up heavy stuff. JM

How is a chimney built? How it the roof built? LM

What are the big white thing next to an ice-skating rink and a big orange thing? This is near where they are fixing a pipe. NO

How to tell machines apart. JW

How they make doorways. ER

Why do they build buildings? KS

Do workers like to take breaks and fix stuff with their hand and materials like wire and tape and stuff? CS

How they build buildings, like the plumbing and the foundation. SL

How do they name the machines, like dump truck, crane, and bulldozer?

Parent Feedback

Parents were very enthusiastic and complimentary at the Share Day. They answered a questionnaire about how they thought their child enjoyed and learned about Construction.

Questionnaire for Parents

We have culminated the Construction Project. We would appreciate your input. Please respond briefly to the following questions below:

1. Did you see evidence of your child's interest in the construction topic (involvement in or excitement about the field trips, classroom, activities, productions, etc)?

Yes, WJ thoroughly enjoyed the topic. He was involved in the building model and thought it very exciting. We knew he really enjoyed all the field trip during the study.

Yes. She was very excited about the work the kids were doing on the green dump truck for the open house. She was also excited about the field trip to the indoor football arena.

SL was extremely interested and excited about building the model crane. He was very excited to see people working and he rally wanted to understand how a building could be built that was larger than the crane.

Yes. She enjoyed the crane building project.

EA's interest in the construction project wasn't really evident, because she shares so little about her school day. She was proud to show me her work at the December open house, Like the large crane drawing, but she hadn't mentioned it previously.

He was excited about the field trip and very proud of the building he made.

Yes she was very interested in stained glass and glass making. Very interested and excited about the trip to the practice facility. Fascinated by progress of buildings being constructed near the school.

Not too much. The field trip he talked most about was the one to the planetarium. He likes planets and thinking about the universe more than construction, I think.

2. Did your child talk about any aspect of the topic away from school? Did the conversations or statement reveal new knowledge about the topic?

Yes. We talked a lot about buildings, architecture, etc. Yes I believe his vocabulary was expanded regarding several arias: Construction, geometry, different types of equipment, etc.

Yes. We spoke at great length about different parts of construction equipment. She knew lots of new vocabulary like the boom of the crane). Also she tells me all about the indoor football field every time we drive by. She seems to have retained everything. She tells me about the tress supporting most of the weight, that it is mainly constructed of steel, concrete, cement. How to earthquake-proof a building. The field trip had a huge impact on her.

His plans for building a pulley and the difficulties involved were a topic of conversation. He also spoke of the arch and how it is built.

Yes we talked about the importance of planning and goals. We also talked about how it's OK to ask for help from others.

EA would willingly answer any questions we had about the construction project, but rarely offered any information. She did learn new information based on these conversations.

Not much.

Yes. She started to build a house in the back yard. NO referred to things she learned about the practice facility and the buildings near UPS to speculate about how other houses were built.

He talked at home about some of the terminology he learned, mostly with respect to machinery and construction vehicles.

3. Did your child like the topic?

Yes - He was very exited about the entire project.

Yes I think she did

Yes!

Yes very much so.

Yes.

I don't think he had real strong feeling either way.

Yes.

On a scale of 1 to 10, I would give it a 5.

Student Portfolios

University Primary School curriculum is child-sensitive and responsive to individual patterns of growth, development, learning, and interests. Children have regular and frequent opportunities to work in informal groups on challenging tasks, and to make decisions and choices. The child's initiative, creativity, and problem solving are encouraged in all areas of the curriculum. For a one and a half-hour period of each day children make choices in Project/Choice Activity time. Teachers help facilitate children in becoming actively involved in research and inquiry about topics worthy of their time and energy. This daily time period and the extended duration of project investigations (two to three months) insures that the activities and assignments are differentiated for abilities in pacing, depth, and breadth. The classroom is also multi-age with student ages being separated at times almost two years chronologically.

Child AH

At the beginning of the project AH was reserved and quiet. She would answer questions very quietly and would seldom initiate conversation or speak in front of the class. Phase 1 of the Project Approach encourages children to be the experts. They recall their life experiences and list them for brainstorming. Children are encouraged to think about their ideas, describing what they remember so their ideas can be compared and contrasted to their classmates' ideas and then categorized. They share their project related personal experiences in a story or representation, again noting similarities or differences in their experiences and critically thinking to categorize the representations. AH gained confidence in a setting where the class paid attention to the details of and gave thoughtful response to her work. Students learn to respect other students' views. AH became more confident and independent in expressing her ideas. She became a bigger risk-taker. Her drawings reflected growth in complexity of thinking, and her questioning skills moved from concrete to abstract.

AH Growth in Thinking - Visible Through Drawings - Simple to Complex

|

AH's simple drawings of roofs.

|

|

AH's more complex and elaborate

drawing of roofs.

|

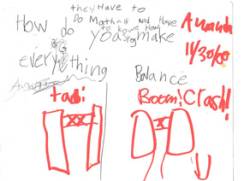

AH - Growth in Questioning - Concrete - Abstract

The Project Approach facilitates students defining the content, in particular selecting the particular question to research and to find the particular direction that interests them.

On 10/31 AH's field notes show her question asked, "Do you make the cranes or do you buy them?"

She interviewed the site manager and noted the answer, "They rent the cranes because when you buy the cranes, it is very expensive." This must have made an impression upon her. AH was very interested in this factual, concrete question and answer. At the end of the project, she wrote that she had learned that cranes are rented.

On 11/7, her level of questioning for the parent expert shows a higher

level of abstraction.

She queried, "Why do you use tools instead of hands?"

For the November 30 field site visit to see the truss and buttress of the Football Practice Facility, her question shows a less clearly defined question with a higher level of complexity.

She asked, "How do you make everything balance?"

The answer that she wrote was, "The architects have to do math and have to know how to draw."

AH's question with a higher level of complexity.

AH - Growth in Independence

AH showed great independence from early on in the year. Most days she would return to the projects that she had started and work toward completion. AH worked slow and carefully on most aspects of the project.

|

||

|

AH demonstrates focus, independence

and persistence at completing her clay representation of a house.

|

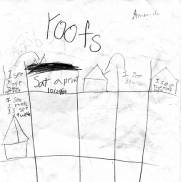

AH independently designed this graphic

organizer to collect data on roofs.

|

She developed her own graphic organizers to record her research findings to her own questions. AH's methods of data collection show planning and critical thinking.

AH - Fewer facets - Multifacets

For the construction culminating, AH spent a lot of Project/Activity time problem solving how to make the crane. She was interested in the crane's cable experiment.

She presented the explanation of this experiment for the culminating open house. We can see from her plans for her speech that she writes a "developed account that reflects some in-depth and personalized ideas" (Wiggins & McTighe, 1998, p. 76).

|

AH's Speech for Parent Open House We did an experiment to see what type of rope was on a crane. We tried a bunch of different materials to lift up a brick and concrete block. These materials (hold up wire and cable) are the ones that held up a brick so we decided that they go on cranes. |

Child JN

JN entered the classroom a month after school began. Project investigations were new to him and work on the construction project was underway. His academic skills were on par with typical kindergartners, but he was less accomplished in many areas and less independent than many of the other students in the class. In most areas he was a concrete thinker. His products were simple and did not demonstrate depth of understanding.

Many children had previous building experiences with sand, Legos and blocks. Some were more proficient than others. JN liked to play with blocks. When it was time to clean up, he would throw the blocks onto the shelves instead of stacking them so that more blocks could fit. The blocks that JN put away would come sliding out on to the floor.

JN - Concrete - Abstract - Growth in understanding directions

|

Blocks sliding out of the shelves.

|

JN organizing the block shelf.

|

The others in the group at several different times told him that he was "doing it wrong" and that he needed to fix it. When he asked how he was supposed to fix the blocks one of the boys said, "You have to stack the blocks so that they don't fall."

JN asked "how" and the other boy said that the blocks have to be even. JN asked what he meant by "even" and the other boy took the blocks and showed him. JN worked at stacking blocks but continued to have difficulty when cleaning up the blocks. Some days later the teacher asked JN to help straighten the blocks due to a shelf repair. He was able to stack the blocks evenly and size the blocks, stacking the long blocks first, then medium blocks and then shorter blocks.

Later, JN and JM, who was also interested in bricks, constructed a block building with bricks. In the beginning JN needed a concrete explanation of how to stack blocks.

JN - Simple - Complex in Building Structures

He moved from simple to complex block building when he worked on constructing the building and represented bricks.

|

JN bulding a structure early in

the project.

|

Making a bulding out of blocks

and representing the brick pattern on the outside.

|

JN - Less Independence - Greater Independence

JN was less independent with what he wanted to draw and write. On 9/27, JN worked 15 minutes with the teacher helping him to focus and sound out the 4-letter word, "maze." (He wrote "maz.")

JN needs the teacher's help to sound out the word "maze."

JN - Simple to Complex

The drawing is a simple circle design of a maze. By November, JN is drawing the interior of a house with a stairway and drawing a more detailed and complex representation of the building at the construction site.

|

JH's simple drawing of the maze.

|

This is JN's more detailed and

complex drawing of a house, showing the inside as well as the outside.

|

By the end of the project, JN would check in with the teacher frequently, but could work with greater independence for longer periods of time. He also would work slow and carefully on a project putting forth his best effort.

JN working slowly and deliberately to make a representation of a stained

glass window.

JN - Growth in Questioning Skills - Concrete to Abstract

JN could not think of a question for the construction project. However, in conversations with his friends, he could ask questions. The teachers pointed out when he was asking a question and called it a question. In October, he was able to express a wondering, "How do you control steamrollers? "

When it was time to go to the construction site on 10/31, with prompting, JN wondered, "How do cranes move?"

For the parent expert talking about tools on 11/7, JN asked, "Do chain saws saw tool boxes?" JN was very interested in machines and his questions reflected wanting to know a concrete answer.

The drill he drew (Phase

2) was very detailed and complex. Before the last visit to the field site

on 11/30, JN questioned, "How do you build a building?" This demonstrated

his authentic desire to understand a complex concept.

JN - Growth in Categorizing and Generalizing Ideas

In the beginning of the project, JN knew that buildings had attics but he did not want to place this idea under the category JN "Parts of a House." He wanted a separate category for "Attics." By December, JN's comment to add to the list about "What We Now Know about Construction" was, "You can make cement with crushed rocks, water, and sand." He categorized his idea under the heading of materials and seemed to understand how his idea fit under a broader heading.

Summary

The two student portfolios demonstrate the wide range of abilities and differences that the students exhibited. Each child was challenged and grew in many areas. The emergent curriculum allowed students to develop their strengths as well as increase skills in areas of weaknesses. Differentiation was achieved in the students' responses to the inquiry-based activities, often designed around the students' own questions.

References Related to Evaluation

Anderson, T. (1996). They're trying to tell me something: A teacher's reflection on primary children's construction of mathematical knowledge. Young Children May: 37.

Brooks, J., & Brooks, M. (1993). In search of understanding: The case for constructivist classrooms. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Klein, M. M., & Toren, G. (1998). Evidence of learning in an inquiry based classroom. Urbana, IL: Unpublished document.

Tomlinson, C. A. (1996). Good teaching for one and all: Does gifted education have an instructional identity?" Journal for the Education of the Gifted. 20, 2, 155-174.

Wiggins, G. & Mctighe, J. (1998). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

|

|

|

||

|

STUDYING

CONSTRUCTION |

EXPLORING

COMMUNICATION |

© 2001. University

Primary School. Department of

Special Education. University of Illinois.

All rights reserved. Credits.