Evaluation, Reflection, and Assessment

Evaluation

The classroom environment enables children to demonstrate what they know through a variety of authentic assessment strategies (exhibitions, demonstrations, journals, group discussions, debriefings, interviews, and conferences). Assessment is constant and ongoing so as to identify students’ strengths and learning approaches as well as their needs. Teachers observe play, watch children drawing, listen to conversations and ask questions. As children explain their thinking, teachers can assess their level of understanding. "Students points of view are windows into their reasoning. Awareness of points of view helps teachers challenge students, making school experiences both contextual and meaningful. Each student's point of view is an instructional entry point that sits at the gateway of personalized education" (Brooks & Brooks 1993, p. 60).

Documentation is vital for assessment. Documentation includes narratives of child to child conversations, child to adult conversations, photo portfolios (photo narratives), wall displays, and written summaries. Documentation offers opportunities for children to evaluate their own work, for teachers to keep parents better informed (knowledge web), and for teachers to gain a better understanding of how children learn. Documenting conversations and representations at the beginning and at the end of the project for the group as a whole and for each individual child gives perspectives of growth in all dimensions including vocabulary, concepts, knowledge, skills and dispositions.

Tomlinson’s “Planning Model for Academic Diversity and Talent Development” (Tomlinson, 1996, p. 162) is a useful tool for examining how children’s responses showed growth. Instead of using the model to differentiate instruction, the teachers have used it to examine how responses to the activities were differentiated among students as well as how they demonstrated growth in students throughout the study. In a project-based classroom, where many activities are open-ended, using Tomlinson’s indicators can show growth. Teachers can demonstrate through child portfolios how children have gone from simple to more complex responses; concrete to more abstract understandings, and less independence to more independence in work habits and dispositions.

In an environment of inquiry, teachers look for evidence of children’s growth (Klein & Toren, 1998). Children’s questions may evolve from general to more specific once children have more knowledge about a topic. They may transfer their learning by making links to other things that they know and with which they are familiar. They may incorporate the new vocabulary into their every day language. Teachers look for growth in fluency of ideas and in ways in which children generate questions, solutions, hypotheses and theories. Teachers look for growth or change in students’ understandings by examining artifacts of learning which include drawings, structures, writings, and conversations. Children may also become more self-directed, more engaged, and may strengthen their dispositions to inquire, to assume responsibility, to persevere, and to take on leadership roles within a group.

The evaluation of a project investigation includes teacher reflections, student self-evaluations, parent-feedback, and an examination of each child’s project portfolio to assess growth and learning. Two examples of children’s project portfolios are included in this document.

References Related to Evaluation

Anderson, T. (1996). They're trying to tell me something: A teacher's reflection on primary children's construction of mathematical knowledge. Young Children May: 37.

Brooks, J., & Brooks, M. (1993). In search of understanding: The case for constructivist classrooms. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Klein, M. M., & Toren, G. (1998). Evidence of learning in an inquiry based classroom. Urbana, IL: Unpublished document.

Tomlinson, C. A. (1996). Good teaching for one and all: Does gifted education have an instructional identity?” Journal for the Education of the Gifted. 20, 2, 155-174.

Wiggins, G. & Mctighe, J. (1998). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Teacher Reflections

Throughout the fall semester teachers watched how children developed their communication skills. The young children in the classroom tended to be interested in themselves. They worked on projects with others as long as the other children did things their way. They had difficulty listening to each other in large group meetings.

Communication, which is so real and ongoing, has abstract components that were hard for children to visualize (properties of sound, telecommunications and computers). Children started the project with a varied background of experiences.

The first conversations showed that a portion of the classroom did not know what the word communication meant. A class survey was taken on January 1:

Have you ever given a message with body language?

The results showed 10 answering “yes”, 15 answering “no.”

The students needed to begin the project by exploring the meaning of communication. Phase I gave children time to become familiar with new terminology. Teachers helped make children aware of communication by labeling components of the communication process. They helped children work out problems with their peers. For example, the teachers would say, “Let’s get together to communicate,” “Who’s going to talk first, and that means the other person is going to listen.” One example of conversation that took place in the classroom follows.

|

LM cried during recess. When the teachers talked to him about it, he said CS wouldn’t play with him. The teachers helped CS and LM get together to communicate.

Another day the same child cried. Teachers facilitated the negotiation between peers.

LM was interested in the fact that communication meant talking and listening. On 4/30, LM stated that, “It takes two people to communicate.” Not all children agreed. CS and BG took issue with communication needing 2 people.

On 5/8 LM maintains, “Communication is 2 people talking.”

His friend NO dictates, “The best thing that I learned about communication was talking face-to-face because it helps people to solve problems. |

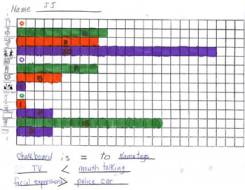

The children came to appreciate good communicating and most seemed to understand that communication is an interchange of thoughts or ideas. They brainstormed a rather complete list of ways to communicate. They counted how many ways people communicated at school. It was interesting to note the diversity of skills exhibited in tally counting and transferring of raw data to bar graphs.

|

||

|

Beginning tally counting with no

cross lines to indicate 5.

|

|

More advanced tally counting skills

evidenced.

|

|

Tally counting using cross lines,

but not always totalling 5.

|

|

Shows that putting data into a bar

graph is challenging.

|

Another big idea was to gain awareness of the relationship of communication

to the means of sending and receiving messages. Through survey questions,

it was evident that children had misconceptions about communication. These

misconceptions were the portals for teaching and extending their learning.

On 1/19, NO thought authors send and receive messages from readers through little holes in the paper.

She developed a survey question, “Do you think books receive a message with little holes in the paper?” One child responded, “yes.” On 2/7, in response to a class survey, “ Can you send a message to a book and have it respond back to you,” one child said, “Yes, if you write in a book and 2 years later you forget, then you can look in the book and it will remind you.”

The class survey taken on January 11 asked,

Have you ever communicated through email?

The results showed 14 answering yes, 11 answering no.

On January 25, the survey questioned,

Have you ever talked on a cell phone?

13 answered yes, 12 answered no.

More than one half of children said they had the experience of sending and getting a message with computers. However some children seemed a little unsure of what part of computers sent messages.

On 1/24, SL asked the survey question, “Have you played a computer game to send a message?” He thought any kind of activity on the computer would send a message.

Many children thought that communication devices could send and receive messages. WJ thought he could send a message to the TV by blowing into the speaker. By 1/26, he didn’t believe he could send a message to the TV. A small group of children went to the TV station to ask questions. When this group reported back to the whole group, it was hard for the children who had not been on the field trip to understand the setting of a TV studio and how television receives pictures as well as sound. The comparison of the TV and computer showed the children not understanding basic differences between each communication device. They knew parts were similar (each have a screen, both played movies).

By the end of the project, 14 children brainstormed ideas indicating that they understood the difference between sending and receiving messages (List of new vocabulary and the Student Communication Topic Web II).

They increased their understanding of the functions of the parts of communication devices. However individual children were at varying levels of understanding and there were still some misconceptions about topics that are difficult even for adults to understand! For example,

CM: a monitor is a kind of TV

CM: RAM is random access memory, which is the brain of the computer.

JP: The motherboard is the brain of the computer.

The children were intrigued by the workings of the computer, cell phone, telephone and emergency signals. However, they didn’t understand exactly how these devices worked. Individual children seemed to understand at varying levels. In Phase 1, during the categorization of their memory stories, AK tried to remember what she did when she sent email. She recalled a telephone line being involved. However, the rest of the class did not seem to agree with her. She also worked through how telephones work. Her progress is documented in the Student Portfolio section. A comparison of the Student Communication Topic Web I and the Student Communication Topic Web II show children’s growth and learning about communication.

How do sounds travel, was a researchable question and big idea. Children had many questions about sound and seemed to understand the most when the experiments made sound more visible. One child, somewhat frustrated, asked, “Why is sound invisible?” Most children increased their understanding of sound as seen by their comments on 4/30.

CO: I didn’t know you could see sound waves in water.

JH: Sound waves can go through walls and hard stuff.

SL: Sound travels in sound waves.

NC: Talking face-to-face uses invisible waves.

ER: Sound waves are invisible.

JP gave an explanation that involved some in-depth ideas of hearing, “When you say ‘Hello’ or something, a pipe or road from your ear to your ear drum moves and your eardrum rattles and it takes in the sound and you hear it.”

Children became more aware of the variety of message senders and receivers. They investigated codes, flag language, Braille, and sign language. Seven children indicated the best thing that they learned about communication was one of these languages. Every child proudly signed songs for their parents.

The last day of school, 3 children were discussing who was going to take home the scenery from one of the plays from Share Day.

| AM: I never get to take something home. CM: But you didn’t work on this scenery. AK: OK, OK don’t let me take it home. I know. You worked on it. You take it home. JP: You helped with the basketball floor. Would you like to take part of it home? AK: I only did a little of the work. It was your idea and you did the most. JP: That’s OK. You take part. I have the other scenery, too. AK: Hey, We communicated to solve this problem. Now, you know once I cut the scenery, it’s apart. |

In conclusion, this project was a good project for helping children gain an awareness of how they communicate with each other and with the world around them. They grew in social and emotional areas as they learned to listen, be sensitive to others, and negotiate by communicating. These are important life skills that far extend the children’s every day learning in kindergarten or first grade.

This particular project investigation was challenging in many different ways for the students. They dealt with abstract concepts that are basic principles of physics. Yet, they enjoyed these challenges because they were pursuing their own questions. They also were challenged by the many opportunities to collect, analyze, and evaluate their data. Presenting results to others helped them to articulate the “big ideas” and gave students authentic purposes to analyze, reflect, and summarize their work.

This project engaged the children for over four months because it was so multi-faceted and provided opportunities for in-depth studies. Almost all of the children broadened their conceptions of communication to include even ways animals communicate.

Student Self-Evaluation

After the project, teachers gave students questionnaires. For those students who needed help sharing their thoughts, a parent volunteer took dictation. The results indicated that many children enjoyed Sign Language. They also demonstrate the children’s strengthening disposition to inquire because many of them still had questions to pursue.

Student Reponses to Questionnaires

Question1: What was the best thing you learned about communication?

|

Child

|

Response

|

Rationale

|

| CS | Telephones | Because I can call anywhere using telephones even though it is far away. |

| NO | Computers | Because you can send a message to someone far away. |

| JB | Sign Language | Because it is good. It helps people. |

| CM | Sign Language | Because it's fun to learn and do it. People who are deaf and dumb can talk. |

| AH | Flag language | Because it helps people communicate far away. |

| KS | The best thing I learned about communication was a Sign Language. | It was fun to learn a sign language. |

| HB | Sign Language | It was fun to learn because I used my body. |

| EA | Telephones |

I don’t know. |

| SJ | The telephone was the most interesting thing I learned. | Because I use it everyday. |

| JK | I can use a computer to send messages. | I don’t know. |

| WJ | Learning how to use email. | Because I play with a computer everyday. |

| NO | The best thing I learned about communication was talking face-to-face. | Because it helps people to solve problems. |

| LM | The best thing I learned was talking to each other. | Because we can share our opinions. |

| JP | About sound waves. | Now I know how sound gets to my ears. |

| ER | It was Sign Language. | Because people who cannot listen, can communicate. Also, it was fin to learn. |

| AK |

Communication is something important. |

I thought that there wasn't that much to communication. There are so many languages: Chinese, Sign Language Hebrew, French, Flag Language and India's Language. |

| BG | Communication | Because communication was talking. |

| MA | Seeing sound waves. | --- |

Question 2: What do you still want to know about communication?

CS: Why is sound invisible?

NO: Why do telephone use wires?

JB: Nothing

CM: All the languages.

AH: No, but I may have one tomorrow.

KS: Nothing

HB: I want to know what is inside a computer.

EA: Nothing

SJ: Nothing

JK: How does a computer work?

WJ: Nothing

NO: Nothing

LM: Nothing

JP: Nothing

ER: How does a computer send messages far away?

AK: Nothing

BG: Talking

MA: No answer

Parent Feedback

The following questionnaire was sent to parents.

Thank you for all you have done to make this a good school year. We are still doing some finishing up activities on the Communication Project. Please fill out the evaluation, if you have time.

1. Did you see evidence of your child’s interest in the Communication topic (involvement in or excitement about the field trips, classroom activities, products, etc)?

NC read the books about communication, the Internet and the telephone. He liked to go on the field trips, especially the TV station and Beckman Institute.

EA definitely showed interest; the most obvious way to us was with her sign language. She also said that she contributed in some of the classroom discussions - talking about email, etc.

Yes! She especially enjoyed the trip to the Beckman Institute and was enthusiastic all semester long about learning sign language.

Yes. LM was especially taken with sign language, radios, telephones, and robots (of course).

2. Did your child talk about any aspect of the topic away from school? Did the conversations or statement reveal new knowledge about the topic?

Yes. He talked about sign language a lot. He uses it at home.

Yes. Again, the Sign Language. She loved this! We have gotten library books that she is pouring over! She rarely is a "performer" at home, so when she shared "Twinkle, Twinkle" in sign language with us, we knew that she was really enjoying this experience, which was all new before this semester.

Yes. LM began questioning the whole topic of communication in many areas, such as how do plants, insects, animals talk to each other.

We talked about how different animals communicate. Also, we had much discussion of Helen Keller.

3. Did your child like this topic?

Yes.

Yes.

Yes, very Much.

Overall, JP liked the topic. She liked some of the field trips. But didn't like the trip to the television station.

Student Portfolios

ER's Growth in Skills in Representing – Simple to Complex

Observational drawings represent children’s thinking. As they progress from simple to complex drawings, they are demonstrating that they understand more about the topic under study. Examining repeated drawings shows growth over time.

ER’s 2/16 simple observational drawing of a computer

ER’s simple observational drawing of sorting boxes

on field trip on 3/6

ER’s simple first observational drawing of a telephone on 3/8

ER’s more elaborate, complex Time 1, Time 2 observational

drawings of telephone on 3/29

WJ’s Growth in Thinking – Concrete to Abstract

WJ was originally confused about the differences between sending and receiving messages. These comments reflect his growth in understanding that one cannot send a message by “blowing into a wire.”

|

Date |

Child's Comment |

Documentation |

|

1/13 |

I communicated by the TV and I was blowing in the speaker. |

Wrote and drew for memory story. |

|

1/16 |

I'm communicating by the TV. It should go with the computer group. You send a message with a pink cord on the TV. If I blow in it, the guy doing cartoons will feel it and know to change the cartoon. |

Conversation at group meeting. |

|

1/19 |

I communicated by the TV and I was blowing in the speaker. |

Contribution to discussion group question, "How did you communicate?" |

|

1/24 |

Can you blow into a wire on your TV to send a message? |

Survey question for classmates. |

|

1/26 |

There are more names on the 'yes' column. But I don't think that's true, any more. I don't think I can send a message to the man on TV by blowing in the wire. |

Conversation with teacher after analysis of survey results.

|

KS’s Growth in Thinking, Framing Questions and Vocabulary – Simple to Complex

KS had difficulty expressing her own knowledge about communication before the study. The teacher continually probed her for ideas. She also demonstrated difficulties asking relevant questions. The sequence of comments below reflect a significant growth in her ability to incorporate new vocabulary words, ask relevant questions, and discuss the topic of communication. However, there are also areas of communication that are still too abstract for her to grasp at this time.

|

Date |

Child's Comment |

Documentation |

Teacher's Comment |

|

1/11 |

I haven't ever communicated.I don't know what to draw. |

Conversation |

The large group problem solving, initial discussion, and brainstorming had occurred.This topic may be too abstract for KS and large group discussions are not as meaningful.The teacher held a conference with KS to find her level of experiences.She chose to draw talking to her sister the next day. |

|

1/30 |

Will the flowers know there are flowers in the box? |

Child's writing and drawing of flowers. |

A conference with KS revealed that she didn't know what to put down for communicating even though on 1/12 she drew herself talking to her sister.So she drew flowers.She was able to combine her interest in flowers with an ill-framed question.With teacher encouragement, she rephrased it to mean, "Do flowers communicate?" |

|

3/7 |

I Love you.How do they mail the mail? |

Child's writing and drawing question before going to the post office. |

A conference with KS showed she meant,"How do they deliver the mail?" |

|

3/8 |

The mailman mails letters to people and he goes to his office and makes more letters then mails them. |

Child's writing and dictating her prediction of the answer to her question of 3/7. |

KS has a simple understanding of written communication and who generates the mail that her family receives. |

|

3/18 |

Do cell phones need to be charged? |

Child's writing of her question for the telephone expert. |

Question is well framed and with more appropriate and complex understanding of phones. |

|

3/20 |

Cell phones do need to be charged. |

Child's writing of what she learned after listening to the expert. |

KS again seems to have a firm and more complex understanding of cell phones. |

|

3/27 |

Why do they have alarms? |

Child's writing of her question for the Fire Training Institute expert. |

Question seems to have an appropriate and more complex understanding of smoke and fire alarms. |

|

3/28 |

I think it (the alarm) senses the fire. |

Child's writing and drawing of her prediction of the answer that she would get from the expert. |

Again KS's prediction shows a more complex understanding of alarms and she is using more complex vocabulary - alarm & senses. |

|

4/4 |

The football stadium is for football. |

Child's writing and drawing of her question for the parent who was going to share the code communicating what he does in the huddle. |

KS seemed to revert to her knowledge from the construction project when the class went to the Football Practice Facility.She also didn't frame a question, but rather a statement of what she knew. |

|

4/19 |

This is me doing gymnastics. |

Child's writing and drawing of her question for the physic expert who was going to answer questions on sound. |

Conferencing with the teacher showed that KS had no questions about sound.It wasn't that she knew everything, but rather she had no idea where to begin. |

AK’s Growth in Skills in Representing and Greater Engagement and Independence

AK continually added detail to her pictures as she learned more about the topic. She also showed an application of literacy skills when she labeled her drawings.

3/6 AK's hurried observational drawing of sorting boxes.

3/8 AK's first observational drawing of a telephone

showing some detail in labeling.

3/29 AK's Time 1 & Time 2 more complex observational

drawing of a telephone.

|

AK more independently representing

the telephone in more than one way.

|

AK very engaged.

|

AK’s Growth in Thinking - Concrete to Abstract

A look at AK’s writings over the course of the project demonstrated how she clarified her thinking.

|

Date |

AK's comment |

Documentation |

|

1/30 |

How does all kind's of communication stuff attach to the person who you are communicating with? |

Question, she wrote. At a conference with her she interpreted the question as How does the telephone sound get from one house to the next house. |

|

3/8 |

The telephone. I think that the phone has a wire behind the part of the phone that you talk on and that wire attaches to an answering machine. Then that wire goes through the answering machine and then it goes under ground and then the wire goes to the person's phone who you are talking to. |

Prediction of the answer to her question. |

|

3/20 |

How do you get phones to connect under ground and get to the person who you are talking to? |

Question for the telephone expert. |

|

3/21 |

The telephone attaches to a wire and the wire goes under ground and then that same wire comes out of the ground and attaches to a telephone that you talk with the person you want to talk to. |

Prediction of what the telephone expert will say to answer her question. |

|

4/19 |

How does sound travel? (writing pictured in Overview) |

Question for the parent who spoke about sound. |

|

4/20 |

The sound waves go through the air and it goes to the sound tower and then bounces back to your phone in 3 seconds but you can't see the waves. |

Prediction of what the sound expert will say to answer her question. |

|

4/30 |

I now know there are glass wires in telephones. |

Brainstorming contribution |

|

5/8 |

Green boxes - the telephone wires go into these green boxes and then it goes to the person you are talking to. |

New communication vocabulary that AK now knows. |

|

5/15 |

On a phone, you dial the numbers and lots of wires on the phone lead to a green box, then to another green box, then to a house. |

AK's comment on what she now knows about her original posed on 1/30. |

|

5/22 |

The Telephone The telephone rings, rings, rings! The telephone is like a person signaling to you that somebody want to communicate with you. And when you talk on the phone it's like someone is transforming your voice to another person. The phone is like a person. |

AK's Telephone poem with the element of personification. |

|

|

|

||

|

STUDYING

CONSTRUCTION |

EXPLORING

COMMUNICATION |

© 2001. University

Primary School. Department of

Special Education. University of Illinois.

All rights reserved. Credits.