Blog post by Deborah Silvis, RA

Reflecting on “What’s Next” for Cyberlearning

Last month I accompanied Mobile City Science PI, Katie Headrick Taylor and Co-PI Andres Henriquez to Washington, DC to present at Cyberlearning 2017 and share information about MCS and our progress on the project so far. The Center for Innovative Research in Cyberlearning (CIRCL) 2017 Meeting brought together researchers, students, and professionals in the fields of Computer Science and Learning Sciences to hear from PIs working on related NSF projects and to discuss “What’s Next” for the transdisciplinary field of Cyberlearning. Other areas of research represented at the series of meetings and keynotes dealt with VR/AR/AI, Data Science, designing learning technologies, teaching and learning Computer Science, Citizen Science, and much more. We had multiple opportunities in formal presentations, smaller working sessions, and informal discussions with colleagues from other institutions to reflect on our experiences implementing MCS so far in 2016-2017 in Chicago and New York City. This was also a chance to engage with prospective questions concerning the future of MCS in the short and long term.

Day 1 MCS Presentations

In the morning on the first day, Katie presented on MCS at a roundtable session on Collaborative Learning. Meanwhile, I sat in on Andres’ roundtable session on Empowering Youth with Technology. He began by situating The New York Hall of Science’s participation in MCS in the broader context of the Queens 20/20 project which aims to engage the youth of a small yet densely populated and culturally vibrant section of Queens (Corona) in STEM related learning. Andres described the reach of the initiative in terms of the many students and families served and how schools were involved in the partnership, highlighting Global Science Academy (GSA)*, the high school that currently serves as the site for MCS implementation in Queens.

Having provided the context for a partnership between the museum, MCS youth (and their school), and our multi-site research project, Andres provided details of facilitators’ and youths’ experiences so far. He emphasized the central idea that young people themselves were defining the matters of concern on the ground in Queens, and he explained how technology and data were framing their learning through the curriculum as well as their identification of hyperlocal community issues such as transit, public health, employment opportunities, public safety, and ecological conditions. Andres shared how, the initial Free Recall Mapping activity, youth had conceptualized their communities as both physically located near school and also in a nebulous everyday space “where I get my sandwich.”

Later that day, Katie and Andres presented together (with Lauren Birney, PI on the Billion Oyster Project) at an Expertise Exchange session on Communities of Learning: Mapping, Moving, and Discovering across Contexts. This talk was well-attended and generated excellent questions and discussion, so much so that the room literally turned into a hot-bed of intellectual activity, and we had to open the door for some fresh air! Katie spoke to what educators need to know and researchers need to consider as they support youth to develop civic literacies around “live” community-scale issues. She provided an overview of MCS, reiterating Andres’ earlier point that the fundamental starting point for MCS is a youth perspective on place, local issues, and change. She provided more details about how this has played out in Chicago and New York in the past six months. Katie posed questions for discussion related to outcomes evaluation of a design based participatory project like MCS and also about understanding the learning goals and determining a set of core experiences for youth to reach these.

Andres added the NYSCI perspective on both how facilitators were trying to balance youth-led identification of hyperlocal issues such as transit or public safety as well as support youth to contribute in an impactful way to widely held concern about public health issues such as air quality. He drew out an example of the problem of air quality (and associated high incidence of asthma among residents) in Queens and suggested that by collecting data on this problem using simple air sensor technology, youth could potentially contribute to techno-social changes such as re-routing the air traffic to and from Laguardia, the airport centered over their neighborhood. This stimulated a lively discussion in which audience members contrasted views of Smart and Connected Cities that are oriented towards professional technology designers developing novel new tools and other orientations that position citizens as experts in the kinds of innovations that might matter to them.

Themes across MCS Presentations at Cyberlearning 2017

One theme that arose in these MCS presentations was the challenge of understanding data. This exists on different levels in MCS; there are not only multiple forms of data (video, GPS, hand-drawn maps, personal time journaling) there is also a relationship between youth-collected data and researcher-collected data. While Andres shared our excitement that youth were surprisingly savvy when it came to understanding the power and utility of data, some audience members were more circumspect, suggesting that transitioning youth from collecting and analyzing to actually shaping persuasive arguments with data would be critical in demonstrating the program’s impact. This was an important point and a rich point of discussion; several colleagues provided useful ideas for how to take the kind of data youth were collecting and manipulating and help them manage and transform it into the kinds of evidence and representations that are persuasive to stakeholders.

Another theme that emerged during these discussions was related to youth using digital and geolocative technologies as part of participating in what is broadly called Smart and Connected Communities (SCC). SCC attempts to imagine, build, and make accessible innovative ideas (for example, the re-seeding of the Hudson Bay with oysters) and cutting-edge inventions (for example, robotic trashcans) that strengthen civic life at the scale of the city. An important point Katie and Andres made regarding this was how the issues and ideas that seem to get consolidated as SCC are often mis-aligned with the hyperlocal matters of concern to local residents. This difference, often between policy makers or government officials and citizens or stakeholders is particularly stark when it comes to young people. MCS, then, intervenes on this disconnect by putting youth in a position to inform decision making about what kinds of innovation would truly make a difference to communities. This resonates with a common issue in Cyberlearning more broadly: a tension between developing flashy new technologies versus using or understanding older tools (such as maps) in new ways. Of course, at the center of all of this (for MCS collaborators) is what all this means for learning.

“What’s Next” for MCS

Throughout the two days, there was an implicit- sometimes explicit- air of uncertainty about the future of Cyberlearning. What would it become in an era of changing public support for science and in light of on-going changes in technology, approaches to teaching and learning, and communities of learners (as well as communities of researchers)? While there is not such a sense of anxiety within the MCS team of collaborators, this was certainly an opportunity to consider our next steps. One issue rising to the top has to do with intentionally integrating cultural framing more fully into the project and curriculum, particularly given the highly diverse resources MCS youth, facilitators, and community stakeholders contribute to the endeavor. Another question involves what new activities MCS might incorporate next and the direction project going forward. Some options identified during the meeting, and in subsequent debriefs amongst team members, could be (a) to scale up and continue the current work with more young people, (b) to develop a set of core activities or concepts that programs would use to implement MCS on their own, or (c) to design novel tools and technologies that continue to innovate and create new activities for youth to engage in digital mapping. Cyberlearning 2017 provided a unique setting and set of human and technological resources to imagine how these different scenarios might play out and what all this would mean for communities of youth learners and the communities of scientific researchers who study them.

*Global Science Academy (GSA) and the names of its staff and students are pseudonyms.

Before you start, these activities are just concepts and curriculum. You may have done them yourself with other adults. However, by seeing how students quickly take to the activities, learning what they think are assets in their neighborhoods, and hearing their arguments for area improvements, you will truly understand the impact of MCS.

Before you start, these activities are just concepts and curriculum. You may have done them yourself with other adults. However, by seeing how students quickly take to the activities, learning what they think are assets in their neighborhoods, and hearing their arguments for area improvements, you will truly understand the impact of MCS.

portation, safety, and varying positive and negative opinions about their own communities.

portation, safety, and varying positive and negative opinions about their own communities.

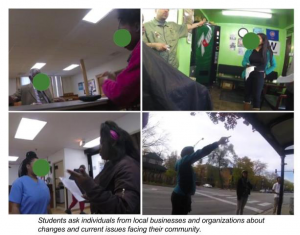

raders were new to the school (our program was held in the fall), and many were new to the area. The Historic Geocache gave them the opportunity to learn in authentic ways about the history and features in surrounding community. The group that met with the pastor learned about the church’s daily breakfasts for the homeless population in the community. After hearing about this, one student asked the pastor how she could volunteer. See what I mean by meaningful?

raders were new to the school (our program was held in the fall), and many were new to the area. The Historic Geocache gave them the opportunity to learn in authentic ways about the history and features in surrounding community. The group that met with the pastor learned about the church’s daily breakfasts for the homeless population in the community. After hearing about this, one student asked the pastor how she could volunteer. See what I mean by meaningful?